Danny Dorling, The No-Nonsense Guide to Equality,

New Internationalist, Oxford, 2012, 176 pp, www.newint.org/books/

Reviewed by Frank Stilwell

New Internationalist has published a series of small books on controversial issues such as world population, world poverty, world food, world health and women’s rights. This latest ‘No-Nonsense Guide’ focuses on equality, making a strong case for this goal to be a much higher priority in public policy and strategies for social progress.

There is a long tradition of arguing for greater equality – in income, wealth, education, social opportunities and, of course, in human rights. One thinks, for example, of classics such as Richard Tawney’s Equality, the writings of British social reformer Richard Titmuss and the more recent books by Richard Wilkinson that describe the damaging social costs that arise from extreme economic inequalities. That these three writers are all called Richard is an odd coincidence – the more important thing that they have in common is a commitment to egalitarian social reform.

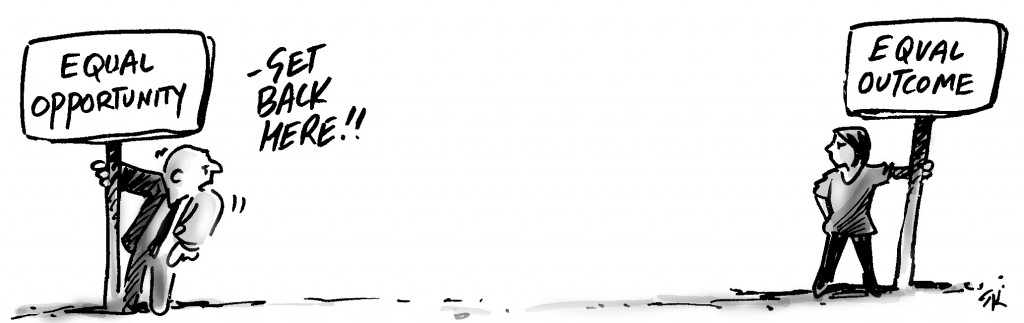

Of course, equality has always been a cornerstone of socialist thought. The eradication of class divisions that systematically reproduce inequalities is an essential part of any left agenda. Even in small ‘I’ liberalism, concern with equality looms large. For liberals, however, it is equality of opportunity that is the goal, which is a much milder goal than equality of outcome. Equality of opportunity can be compatible with continuing extremes of poverty and wealth – just so long as everyone has an equal chance to get to the top. For more strongly committed egalitarians, that outcome is quite unacceptable.

Equally contentious are the means by which greater equality might be achieved – whether through redistributive tax reforms, policies to reduce the range of pre-tax ‘market’ incomes or through a more radical assault on the current concentrations of political economic power. Some say we should just give up because it is all too hard, but then all the other socio-economic problems would become so much more difficult to resolve. These are circumstances in which a thoroughgoing reassessment of equality is appropriate.

The reassessment is certainly timely. Relentless tendencies towards greater inequality have been much in evidence during recent decades. The situation had been quite different earlier in the twentieth century, when inequalities had been kept in check – sometimes even narrowed – by the efforts of trade unions and social democratic governments. High union coverage of the workforce created the capacity for greater solidarity in advancing the collective interests of labour and reducing exploitation. Concurrently, social democratic principles gave reforming governments the resolve to narrow the gap between rich and poor through progressive taxes and welfare state expenditures.

In the last three decades we have seen a sustained assault on these ‘ameliorating’ elements in capitalist society, leading to more ‘capitalism in the raw’. This has been a key element in neoliberal ideology and practice. Higher incomes for these at the top are said to be justified as ‘rewards for excellence’ and because they foster ‘incentivation’; while lower incomes at the bottom assist ‘cost competitiveness’ of industry and create incentives to work harder and longer. The arguments don’t stand up well to critical scrutiny. As the political economist J. K. Galbraith (Snr.) once remarked, they presume that the rich work harder when their incomes are raised while the poor work harder when their incomes are lowered!

In the last three decades we have seen a sustained assault on these ‘ameliorating’ elements in capitalist society, leading to more ‘capitalism in the raw’. This has been a key element in neoliberal ideology and practice. Higher incomes for these at the top are said to be justified as ‘rewards for excellence’ and because they foster ‘incentivation’; while lower incomes at the bottom assist ‘cost competitiveness’ of industry and create incentives to work harder and longer. The arguments don’t stand up well to critical scrutiny. As the political economist J. K. Galbraith (Snr.) once remarked, they presume that the rich work harder when their incomes are raised while the poor work harder when their incomes are lowered!

These inegalitarian neoliberal beliefs have had strong traction in the political arena, notwithstanding their conceptual incoherence. Their embrace has resulted in policies that have put trade unions and the welfare state under the gun. One should hardly be surprised that inequality has increased as a result – capital makes capital, while poverty becomes self-perpetuating when the welfare state is weakened.

Is there a case for – and the possibility of – driving change in exactly the opposite direction? The author of this latest New Internationalist ‘no-nonsense guide’ certainly thinks so. Right from the very first page, Danny Dorling nails his colours to the mast of the good ship Equality. He says he is going to make a positive case for equality, rather than dwell on the negative consequences of inequality. He does not consistently carry this through, but no matter – these twin aspects of equality and inequality are two sides of the same coin. The case for greater equality rests, to a significant degree, on the social benefits that predictably result – less crime and violence, better physical and mental health, improved environmental quality, and so forth. Dorling argues that the quality of interpersonal relations and children’s upbringing also depend significantly on the degree of equality in society. The book even includes a section on ‘why equality matters for lovers’.

The author’s reasoning is complemented by an array of statistics on inequalities between and within countries and substantial evidence of their correlation with other social and economic data. He shows that there are dramatic differences between nations in the extent of inequality. He also shows, as does The Spirit Level by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, that there are clear connections between these differences and the incidence of various social problems – ranging from homicide rates to social immobility and, ultimately, unhappiness. Yes, the evidence indicates that more equal societies are generally happier and more sustainable societies.

Conversely, there is little evidence of any reliable connection – as proponents of ‘incentivation’ commonly claim – between inequality and productivity. The neoliberal argument for inequality is revealed for what it is – an ideology to legitimise what is otherwise socially unacceptable and morally repugnant, the triumph of greed over social purpose, and of class interests over our collective wellbeing.

So what is to be done? The bulk of Dorling’s book is concerned with making an ‘in principle’ case, leaving relatively little time for consideration of practical steps towards social change. This is a pity. The last chapter, however, does put a notably strong emphasis on the case for a guaranteed minimum income policy. Indeed, this is a progressive reform whose time should have already come.

The implicit message throughout the book is that the main driver of change is ‘getting the message across’ – the message that we would all benefit from more egalitarian outcomes. At one stage the author even claims that ‘greater equality is in the interests of the rich as well as the poor because the rich then benefit, among many other things, from more social cohesion and trust – not to mention less crime and competitive stress’ (p.145). But it is a tall order to imagine ‘across the board’ support for radical redistribution, is it not?

New Internationalist is an organization that deserves full credit for commissioning and publishing this worthy contribution to public debate. Marshalling an array of arguments and evidence to support the case for equality, as this book does, is very useful. However, the hoped-for consensus on the benefits of an egalitarian society is likely to remain elusive. Perhaps the real impact of the arguments and evidence lies in their use in an ongoing class struggle. The social consensus on the benefits of equality may then follow, rather than precede, the achievement of a more egalitarian society.

Further reading:

The New Internationalist’s book, ‘Equality’, can be ordered by mail from New Internationalist, Reply Paid 64196, Adelaide, 5000; Phone:1800 111 212; Web: www.newint.com.au International orders: www.newint.org/books

NI has published twenty seven ‘No-Nonsense Guides’ on a variety of important issues (priced at $20 each for each 144 page paperback). It currently has the following offer: buy any three ‘No-Nonsense Guides’ and GET one Free! – i.e. for a total price of $60.00. For post and packing add 10% of total goods ($9 minimum charge, $25 maximum).

Also recommended reading: R.Wilkinson and K. Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Nearly Always Do Better (reviewed in Australian Options, No.58, Summer 2009-10).

This review originally appeared in Australian Options #70 Spring 2012 – http://www.australian-options.org.au – and is reproduced with permission.